Devlog 2: Jobs, Decks, and Difficulty

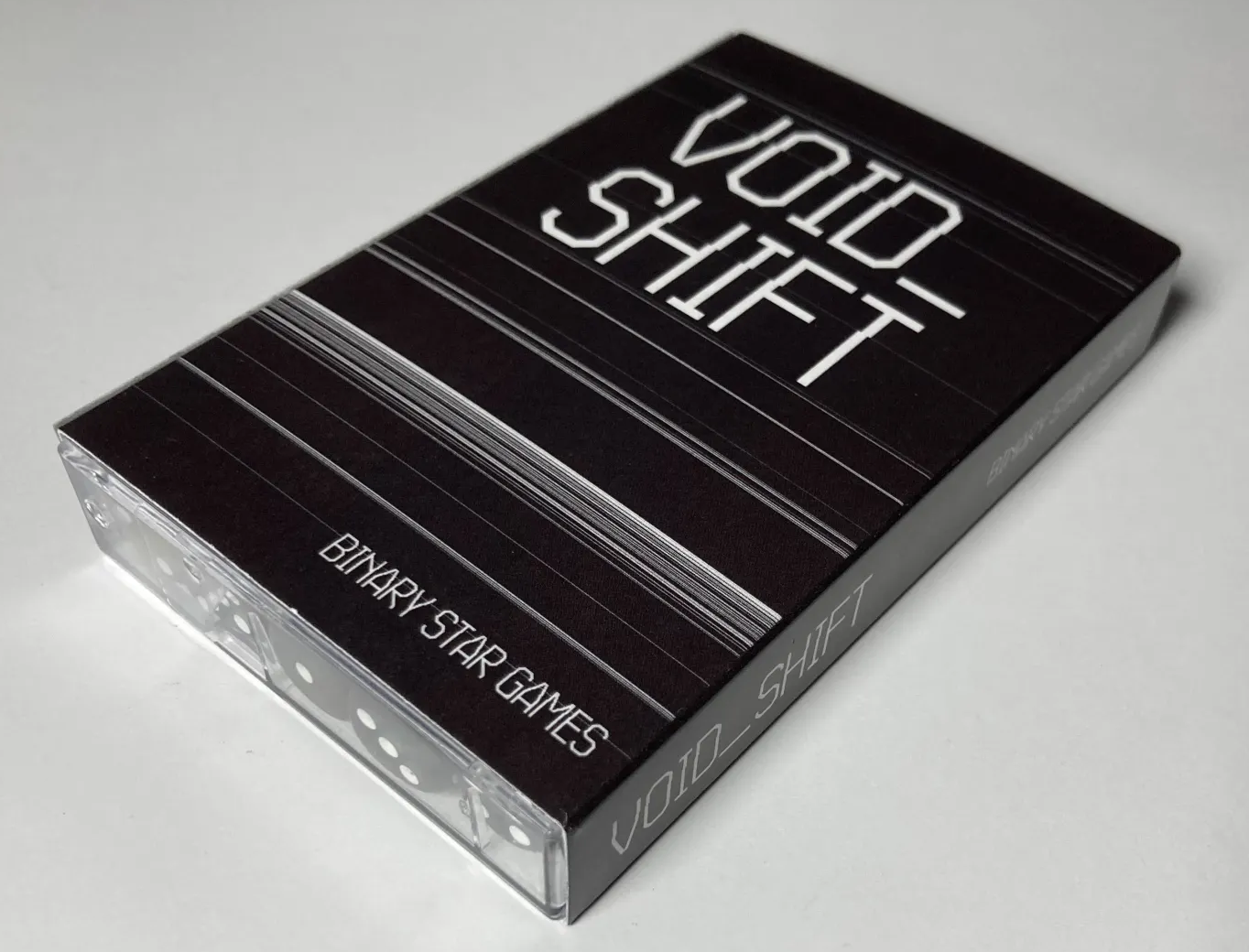

Hi there! Up front, VOID_SHIFT physicals are out!

It’s a cassette case with a (nicely printed) deck, five dice, a J-card in the case with instructions, and a lovely O-card that slips over the case. You can get them at my store for physicals! (And while you’re at it, take a gander at the Black Friday sale - everything else in the store is 20% off. Remember, shipping’s free in the US if you spend $50+!)

In Devlog 1, we got into the basic building blocks of cards and jobs. That’s all well and good, but at that point I needed to draw the rest of the owl: basic concepts only get you so far, execution is what really matters. I blocked out a prototype deck with those principles and started thinking about what I wanted jobs to look like.

Jobs

A job is a card, front and back, that tells you what you’re doing. It has a few distinct requirements:

- Thematically distinct from other jobs

- Works within the conceptual confines of Mechanical, Chemical, Electrical, and Software and should reward having a good mix

- Does at least one thing to make you interact with the job differently

- Has to fit on one card

The first one (thematically distinct) is pretty self-explanatory: ideally you don’t have two jobs that seem like the same job.

The second one (working within proficiencies) is a little tougher, because that’s a fairly broad mix of capabilities. In general every card should include all 4 of them, but the degrees don’t have to be evenly split, and in fact probably shouldn’t be 100% even.

Jobs treat tasks differently to gate this. Compare the following:

- Single-skill tasks bottleneck things by making one specific affinity required.

- Double-skill tasks (aka two capabilities tick down one die) are more flexible: if two skills are usable with equal weight, then effectively 75% of workers can contribute equally.

As opposed to other kinds of tasks that let players be a little strategic with the approach:

- AND tasks require you to basically do two single-skill tasks in parallel. This means that the same 75% can contribute to start, but it goes down over time because when one completes it turns into a single-skill task.

- OR tasks are similar to double-skill: two tasks are listed and you need to complete one of them. The trick is that in theory you can waste time approaching both sides of the “or” equation when only one of them matters.

So the first kind emphasize specific requirements, while the second kind are more flexible to your deck.

The third requirement (different kinds of interaction) is where we start to get into exception-based design on the scenario end. In keeping with point #4, it had to come across as very coherent very quickly. So I identified a few mechanical threads from the mechanics that I could tug on:

- Number you can draw per shift

- Number you can play per shift

- Amount of time remaining

- The Fail/Succeed/Succeed+Exhaust ternary

- The Rest/Tired/Exhaust lifecycle

- Task quantities going up instead of down

And ideally they should mix in with the theming, because that’s the point.

And the fourth requirement (has to fit on a card) means they have to be concise, or if they’re not, they have to come before fewer tasks.

So once I had a job or two, I playtested a bit. And for the most part, it worked! But just working isn’t the end of it. There was one key bit I hadn’t really dug into yet: the building part of deckbuilding. So I buckled down there.

Building a deck

The key from there was making sure the actual deck was interesting to build. There are three kinds of cards:

- Workers who do the actual thing you need to win.

- Mgmt who does more “meta” stuff: buffs, debuffs, card draw, putting cards on top of the deck, etc.

- Tools which augment workers directly.

My palette was a few specific mechanics:

- Proficiency buff/debuff

- Exhaust buff/debuff

- Card draw

- Putting cards on top of the deck

- Tired vs rested

- Exhausting cards (and un-exhausting them)

- Decommissioning cards

So I designed (and redesigned, later) cards with a few basic strategies in mind.

- Going “wide”. Just putting as many workers on the field as possible and having them go at the problem.

- Going “tall”. Putting a smaller number of workers on the field, but having them be better at what they do.

- Risks and mitigation. Putting cards on the field that can create bad outcomes in certain conditions along with other cards that could help manage that risk.

- Risks and leaning into them. Putting cards on the field that can create bad outcomes, but other cards that get better when those bad outcomes happen. So it’s “mitigated” by being a “either way I get something out of this” situation.

So thinking about the conjunction of these and the general flow of the game as established in devlog 1, you can see a few properties emerge:

- At the base level, the nature of playing a card is an opportunity cost. So any effects - especially those from less “direct” cards like mgmt/tools - have to be weighed against “could I have just played another worker”.

- Exhausting a card is bad in shift 1, not great in shift 2, and (usually) not a big deal in shift 3 because of how far you are from reshuffling when you start a new day. So cards where a drawback is exhaustion will improve throughout the day.

- Card draw is in an interesting place because as written, unless you do something to change it or unless the job changes this, you will draw your whole deck throughout three shifts and you can’t play more than the limit. So card draw’s value here is to synergize well with cards that either want to be played earlier in a round or cards that put themselves or other cards on top of the deck.

- Decommissioning is a death-spiral kind of mechanic because you’re constantly regenerating your deck every day, so you’ll have less cards to work with. So cards that do it had better provide something worthwhile in return. As such, decommission is similar to exhaust but on a timescale of the whole game rather than a single day: the closer you are to the goal, the less it matters to not have a card for the rest of the game and the less problematic the downside is.

Just as importantly, I had to set a few guidelines for each of these.

For workers, each worker always has two technical proficiencies they can do, one better than the other. Workers come in a few major varieties:

- On-curve (usually proficiencies are 4 and 3) and have a more “neutral” trait. (In prototyping, I had a few “boring” ones that didn’t have traits, but I ditched that idea almost immediately.)

- Over-curve (usually proficiencies are 5 and 2-4) but have a drawback. High reward, but riskier.

- Under-curve (usually proficiencies are 3 and 2) but have a very good trait. If the trait buffs their proficiencies, sometimes it can bring them as high as over-curve (5 and 4) but without the drawback.

Usually exhaust is 1, but sometimes it’s not if a particular card interacts more with on-Exhaust mechanics - for example, if a character does something bad on Exhaust, they’ll have higher Exhaust.

Generally speaking, workers never have “active” abilities: they have things that are triggered by their own actions or the presence/actions of others.

Mgmt cards always have “meta” abilities that are activated proactively instead of reactively, and they can really set the tone of a deck as a result. As a rule, though, they can never themselves do the work: you need actual workers for that. There’s only a few of these in here because of that. For tools, I went back and forth on them in development, and they’re relatively minor because as with mgmt, I decided more kinds of workers probably made more sense than a ton of tools. They provide a persistent buff to workers throughout the day and some of them interface with certain strategies noted above.

Difficulty curve

So one thing I try to emphasize in just about any game I make is that I want it to be possible to be played “naïvely”. Which is to say, for the majority of RPGs, I don’t think you should have to be like…really good at the game to generally “succeed”.

Now obviously that’s a little less important with a card game, doubly so with a solo one! If you make a bad deck or play it badly or get screwed by the dice, it’s over in like 20 minutes. But nonetheless, I don’t really provide any signposts as to what you SHOULD do when making a deck. As such, my balancing criteria for a given job was as such: if I can juuust barely win (like, somewhere on day 6) with a largely random deck (aka I just shuffled it and picked the top 15) that’s being played well, then it’s probably fine. (This also helped me identify cards that didn’t have much significance outside of the context of others: I wanted each card’s value to be clear enough by reading it, with any synergies as an added bonus for being smart.)

Why did I take this approach? I figure it’s easier to scale difficulty up than it is to scale it down: it’s trivial to make it 4 or 5 days, or go for a “high score”, or do multiple jobs in a kind of “campaign” with the same deck, or add on extra challenges (like no mgmt or no tools or such in a deck). I would imagine it’s harder to know how to scale down in a way that makes the game easier without trivializing the game.

So hopefully this all makes sense! Again, physicals are available at my store: https://shop.binarystar.games/products/void_shift Let me know if there’s anything you want me to expand upon.

(And while you’re at it, give its sister game a follow. Coming Zine Month 2026!)

Get VOID_SHIFT

VOID_SHIFT

Assemble your deck and don't get fired.

| Status | Released |

| Category | Physical game |

| Author | Binary Star Games |

| Genre | Card Game |

| Tags | Sci-fi |

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.